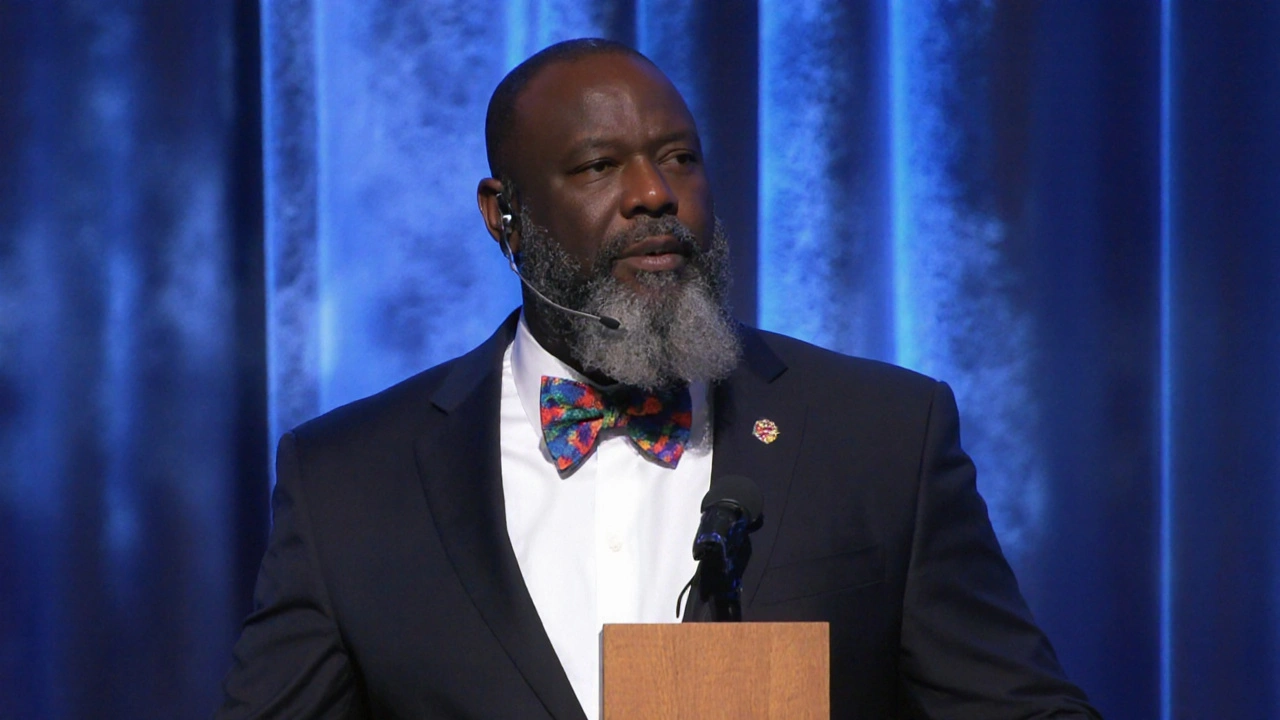

Voddie Baucham Faces Eligibility Questions After SBC Presidency Nomination Request

When Voddie Baucham confirmed in March 2022 that a group of Southern Baptist leaders had floated his name for the convention’s top job, the reaction was immediate. The dean of theology at African Christian University in Lusaka found himself at the centre of a what‑if scenario that pits his overseas missionary status against a role traditionally held by pastors based in the United States.

Why the nomination matters

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) presidency is more than a title; it shapes the denomination’s annual meeting agenda, oversees major agencies, and serves as a public face for one of America’s largest Protestant bodies. For a conservative voice like Bauch’s—known for cultural apologetics, strict biblical interpretation, and a prolific book catalogue—being tapped for the job signals a potential shift toward a more internationally focused leadership.

Supporters argue his experience on the ground in Africa could broaden the SBC’s perspective, especially as the denomination grapples with declining membership at home and seeks new growth markets abroad. Critics, however, point to the SBC’s bylaws, which traditionally require the president to be a pastor of a local church in the United States, raising the question of whether a full‑time missionary can meet the eligibility criteria.

Eligibility and the missionary dilemma

The SBC’s Constitution states that the president must be a “minister of the gospel” who is “in good standing” with the convention. What that phrase actually means has sparked heated discussion on forums, at regional meetings, and on social media. Some argue that being a full‑time faculty member at a university—regardless of location—counts as ministry, while others maintain that the role should be filled by someone who can physically attend the convention’s annual meeting and respond quickly to crises that arise in the United States.

Baucham himself has been candid about the ambiguity. In interviews he noted that his move to Zambia in 2015 was driven by a sense of calling, but he also recognised that the SBC’s leadership structure may not be set up for a president based overseas. He said, “I’ve been asked, I’m honored, but I’m not sure the bylaws were written with someone like me in mind.”

Legal scholars within the SBC point out that the denomination could amend its constitution if a consensus forms around a more global leadership model. Yet any amendment would require a two‑thirds vote from the messengers—a high bar that reflects the deep‑rooted preference for domestic oversight.

Meanwhile, the conversation has rekindled interest in the SBC’s historical stance on missions. In the 19th century, the convention funded overseas work through the International Mission Board, yet its top officers remained American. Today, with missions staff often spending years abroad, the tension between governance and global outreach feels more pronounced than ever.

Beyond the legalities, Baucham’s potential candidacy has stirred emotions among conservative Baptists who admire his uncompromising theological posture on issues like gender roles, family values, and cultural engagement. His preaching style—direct, unapologetic, and peppered with personal anecdotes from his nine‑child family—has garnered a sizable online following, making his name a rallying point for those who feel the SBC is drifting away from its roots.

Opponents, however, caution that a president heavily identified with a single theological niche could alienate more moderate factions within the convention. They worry that focusing on cultural apologetics might sideline pressing internal concerns such as clergy abuse scandals and financial stewardship.

What remains clear is that Baucham’s name on the nomination list has forced the SBC to confront a question that’s lived in the background for years: Should the denomination’s highest office reflect its growing international presence, or stay firmly anchored in its American base? The upcoming annual meeting will likely see informal votes and heated hallway conversations, but any definitive decision will probably require a formal amendment—a process that could take years.

For now, Baucham continues his duties at African Christian University, teaching future pastors and missionaries while his family—wife Bridget and their nine children—adjusts to life in Lusaka. Whether he will throw his hat into the ring, wait for a rule change, or decline altogether, his brief brush with the SBC presidency has already left an imprint on the conversation about how a 19‑century denomination navigates a 21st‑century world.

I feel a deep sorrow seeing our beloved tradition being tossed aside by those who claim to be "progressive". The very notion that a missionary overseas could become the head of our convention reeks of a moral decay that we cannot ignore. It is a direct attack on the sanctity of local pastoral leadership, and it should be condemned with all the fervor we possess. We must stand firm, even if it means sounding unpopular or out of step with the trendy narratives of today.

The whole idea is a betrayal of our national heritage. How can an Indian-educated, foreign‑based pastor possibly understand the pulse of American believers? This is just another attempt by elitist globalists to dilute our core values.

Hey folks, let’s keep an open heart about this! Even if it sounds strange, the global perspective could bring fresh energy to the SBC. I’m excited about the possibilities, and I truly believe we can grow stronger together. Let’s not let fear stop us from exploring new horizons.

The proposal is a dangerous move that undermines the authority of domestic pastors. It shows a lack of discernment and respect for the established order.

The conversation surrounding Voddie Baucham’s eligibility invites us to reflect on the essence of ministry in a globalized world. Ministry, at its heart, transcends geographic boundaries and seeks to embody Christ’s love wherever He is needed. Yet, institutional frameworks like the SBC’s constitution were drafted in a different era, with assumptions that may no longer hold true. When we examine the historical context, we see that early Baptists were missionary pioneers who ventured far beyond their homelands. Their zeal was not confined by national borders, but rather propelled by a conviction that the Gospel must reach every tribe and nation. In contemporary times, this same spirit calls us to reconsider whether a president must be physically present in the United States to serve effectively. The practical challenges of a president based in Zambia are real, especially regarding timely decision‑making at annual meetings. However, technology now offers avenues for remote participation that were unimaginable half a century ago. Moreover, the symbolic value of electing a globally situated leader could signal a profound shift toward inclusivity, acknowledging the growing importance of the Global South in the body of Christ. Critics fear that such a shift might marginalize domestic concerns, yet the very fabric of the church is woven from diverse experiences. By embracing a broader view of leadership, the SBC could inspire new partnerships and revitalized mission strategies. It would also align the denomination with its own historic commitment to worldwide evangelism. Nonetheless, any constitutional amendment requires a supermajority, reflecting the gravity of altering long‑standing governance. The dialogue must therefore balance respect for tradition with an honest assessment of present realities. In doing so, the SBC may discover that the question is not merely about eligibility, but about identity-whether it remains a purely American institution or becomes a truly global fellowship. This reflection invites every messenger to pray, discern, and envision the future that honours both heritage and horizon.

Building on the thoughtful analysis above, I’d like to emphasize the strategic implications of a globally‑situated president. From a governance perspective, leveraging cross‑cultural insights can enhance our missional agility. Moreover, integrating remote decision‑making protocols could streamline crisis response, reducing latency inherent in physical travel. The synergy between theological depth and operational efficiency is crucial for sustaining growth in diverse contexts.

This is ridiculous.

Ah, the venerable tradition of tearing down fresh ideas-so timeless, so elegant. One might wonder why we cant simply keep doing the same thing over and over, because, you know, change is a scary word.

I appreciate the nuanced perspectives presented. It is vital that we approach this matter with both respect for our heritage and openness to the global body of Christ.

While the debate is rife with emotion, the pragmatic concerns remain unaddressed. A clear, data‑driven assessment would serve the convention better than rhetorical flourishes.